Coming from a background in web development, I’m very much used to delivering software in quick cycles. Features are broken down to their core, developed and tested and then released into the wild. Sometimes a product is deployed to production customers dozens of times in a day. In its turn, this methodology facilitates and thrives on a quick feedback loop, with small iterations on a single feature being the norm.

But is mobile any different?

Development workflows for (native) mobile apps are a little diferent, yes, mostly because of App stores themselves, which require review times that can take full weeks before your app is in customers’ hands.

The languages we use to develop these apps also make shorter feedback loops more difficult. It’s a lot harder to develop using a TDD-based workflow when you have to compile code every time you wish to run your test suite.

How to manage Release Cycles

Lately I’ve found a good approach to manage release cycles and beta testing. Here’s a simple overview of the workflow I’ve adopted when developing the Clubjudge app:

- Develop and test the feature

- Integrate the new feature with the current stable branch

- Publish a beta version

Development & Testing

A feature branch is created in the Git repository, based off of the current master. The master branch only contains code that has been proven to work through automatic and manual testing by the developers (it can, of course, still contain bugs) and that is well integrated into the app’s UI, so it is always deployable.

As the feature is developed, the suite of unit tests is expanded to cover its use cases. It’s a little more difficult to use the classic red-green-refactor TDD cycle, because XCode does a lot of the legwork for you, but it’s still doable in a relatively rapid, iterative fashion.

For writing the actual unit tests, we use the excellent Kiwi BDD framework. Writing tests in a BDD style is a natural fit for our team (and personally, my favorite way of authoring tests), since we use the same style across all our other applications, written in Ruby and Javascript.

Integrating the new feature

Once the feature is ready, a Pull Request is submitted to our Github repository.

The time code spends in a Pull Request is very important. For one, it presents an opportunity for other members of your team to review your code, pointing out possible problem areas or discussing some novel technique that was used.

While the team is reviewing the code, a new build order is automatically issued on Travis CI (free for open source, paid plans for closed source), where the new code will be tested against the current master branch. This build process does a lot of work for us: It downloads all third party dependencies (via Cocoapods), compiles the project’s target and runs the unit test suite.

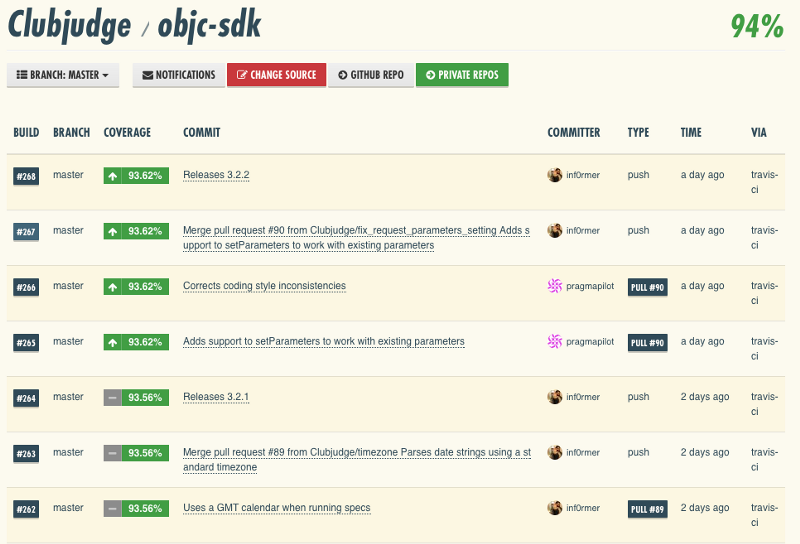

The xcodebuild command-line tool (we use Facebook’s xctool) compiles the project with the GCC_INSTRUMENT_PROGRAM_FLOW_ARCS and GCC_GENERATE_TEST_COVERAGE_FILES flags set to YES, so code coverage reports are generated. Using a simple Ruby script (written by Cocoanetics, available on Github), coverage data is uploaded to Coveralls (also free for open source and paid for closed source), which lets us quickly look at how well the project is covered by unit tests. Here’s an example from our open-source Objective-C SDK for the Clubjudge API:

If the build passes on Travis and the coverage report is good (a rule of thumb is that it should at least remain at the same %) the Pull Request is merged and makes its way into the master branch.

Beta testing the feature

Once the new commits are picked up on master, Travis kicks off another build process. Once this is complete, a simple shell script creates a Release build, signs it and then uses Testflight’s API to publish the build. From then on it’s simply a matter of allowing testers access to the build and watching the reports come in! We like to keep this last step manual, as not all builds of master should be beta candidates. The whole process of setting up Travis to compile builds and send them to Testflight is in this gist.

Wrapping it all up

While it’s true that all of this process takes a while to fully get up and running, I believe it automates a lot of boring tasks and lets us develop mobile software in a way that is closest to the agile spirit already very widespread in web development circles. It lets our team worry about coding and delivering value to the end user while enjoying shorter feedback cycles, and allows us to follow a tight release scheme that maps closely to our in-house development sprints.

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out to me on Twitter. I’m @informer.